Sometimes I get worried about teaching art. Particularly in reference to showing artworks to students. The conventional way is by showing slides of famous works. Often in an institution students see the same slide of the same artwork for decades without any variation of perspective or context. This is more than a pedagogical issue of how to make artworks truely exist for students, for me it is an emotional obligation to be faithful to larger things of which I have become part.

When I look at certain artworks they make me actually miss the makers (and often I have never met them and never will). I miss them like dear friends I knew, I loved, and have since passed away. These artworks are friends who have passed on, and I feel a strong loyalty mixed with tenderness towards showing them as an instructor. I feel as if I were accountable to them, as if I could make them proud or disappointed of me and my actions.

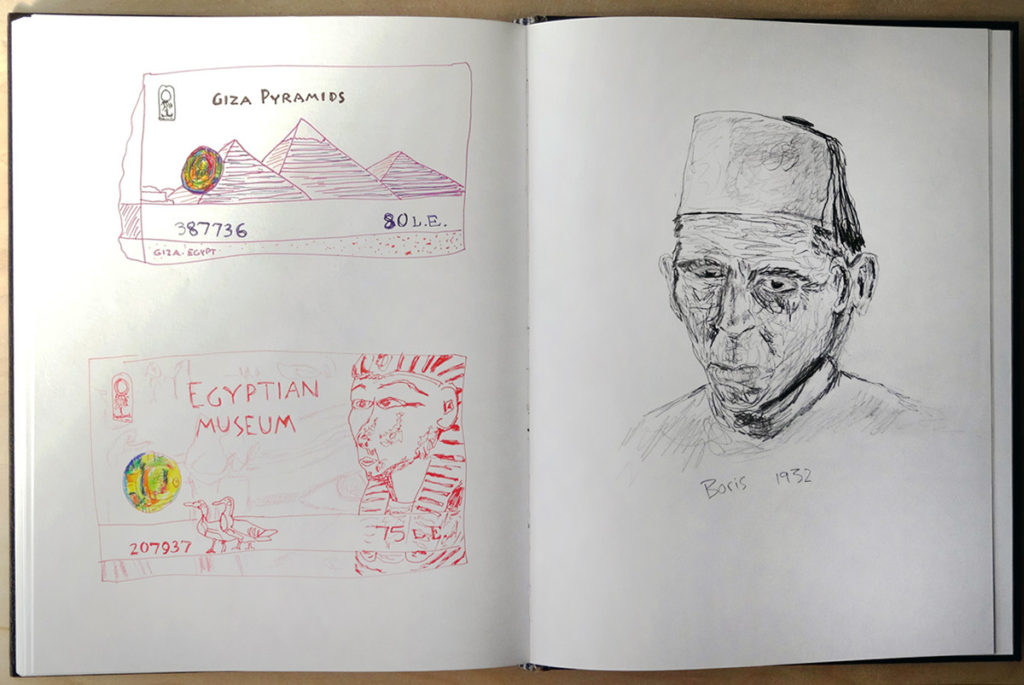

Its better this way, along with the entire body of my artwork presented here, is a response to that space of loss and non-representability. In these works I am asking how to proceed with authenticity towards some of the things I love the most, want to share the most, but often cannot represent for others.

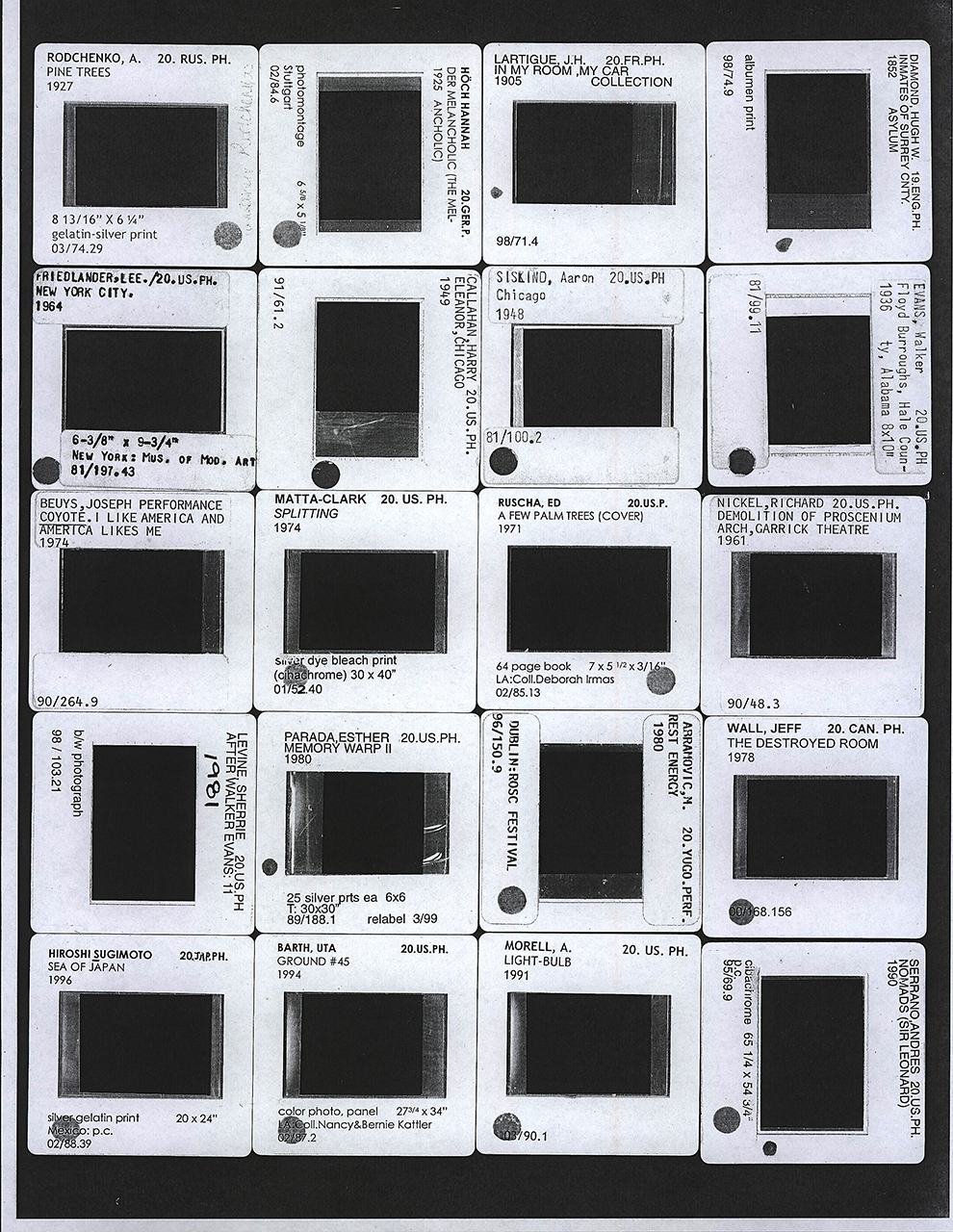

Slides are/ were the jeweled skins of the things and places they image, not pixels and not prints. They are the fragile positives of light bouncing off the original artworks themselves (in the best case, otherwise they were duplicates of images in books).

My photocopied slides are emphatic about their status as a stand in for the real. They are a copy, of a duplicate, of the living artworks in the world. Artworks labored upon and loved by others.

The photocopies I present are fair. Fair in the matte black opacity they offer in lieu of the seductive transparencies that slides put forth. What is lost, obscured, or even forbidden by slides is the experience of seeing an artwork:

Walking up marble steps rubbed away by generations. Noticing well dressed, sophisticated patrons, feeling insecurity, and then maybe stumbling upon González-Torres’s Untitled (Portrait of Ross in LA), and eating some. Sneaking a gentle touch of the surface of one of Van Gogh’s paintings of his bedroom. Becoming infatuated by Callahan’s humble 8×10 photographs of his wife. Missing Andy Warhol, and knowing he was sweet and severe as you look upon his Silver Car Crash. The surreality of being eye level with Tasset’s Cherry Tree, and the matter of fact cheat of gazing upon any Ruscha book under glass, but not being able to touch it’s pages.

I can go on and on. The only time slides are fair for to me is with iconic performative works from likes of Beuys, Bas Jan Ader, and Ambramovic. Slides of these performances are appropriately dual failures and potencies. Slides of these artworks are anamolies in that they can potently distill an entire work into a single rectangle. Each slide becomes a willing and conscious participant in representing something that is now only a representation. I like these slides but I feel as if they should be called by another name to mark them as separate from the flat, charlatan reproductions of artworks like Étant donnés.

So when I teach and show slides I feel it always as a deep slight to the artist and the viewer.

The only response I could muster to this problem of looking at art was to pick 20 slides, (not my top 20 but what I had at the time), and photocopy the image away leaving the identifying text. A fair-ish version of looking at artworks properly. As you look at the sheet of 20 slides they read as a block of small cells darkened while their occupants rest. Eventually, as you linger over each copied slide you see a dense black that has a palpable depth and texture like a room you wake in at night.

Benjamin Martinkus , artist & educator